WHAT IS THE TAO?

Page Info

Name 관리자 Comment 0items View 2,902 Date 25-05-20 16:04Contents

“WHAT IS THE TAO?”

<Editor's Note> This is the interview of Prof. RHEE Dongshick with announcer in the TV talk show aired on Dec. 8, 1990 on the Korea Educational Broadcasting System (EBS). It was translated by Dr. YUN Woncheol (State University of New York, USA., at that time).

MC: Good evening. This program is designed to provide a reflection on the meaning of our life. Our topic tonight is the Tao.

We would call a person who is extremely good at something a "Master of Tao." And to a person who is absorbed in thinking, we would say in joke, "Are you practicing the Tao?" Tonight, we are to think about the true meaning of the Tao, and how it influences our lives.

Our guest tonight is Dr. RHEE Dongshick. He is a psychiatrist; but has also studied the Eastern philosophy and become a reputable authority in it, and advocated the significance of the Tao all over the world, including the West. Good evening, Dr. RHEE.

RHEE: Good evening.

MC: There must be reasons for you, as a psychiatrist, to have been devoted to the study of the Tao. What aspect of the Tao has fascinated you? What does the Tao mean?

RHEE: You introduced me as an authority in the Eastern philosophy, but I don't deserve that title. I simply happened to be interested in the Eastern philosophical tradition while I was studying psychiatry and psychoanalysis in the United States, and since then have been making an effort to have an understanding of it.

Eastern people, including Koreans, would regard the Western tradition as the best, without appreciating the value of their own tradition. I thought there must be something significant in our tradition when it has a history of five thousand years. So I began to study Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, etc. and found that they have suggested excellent ways of treating mental problems. Their ways seemed to be better than that of the Western psychiatry or psychoanalysis. Indeed, I think the Eastern tradition contains an ultimate solution. In an effort to advocate the excellence of Eastern tradition, I made presentations on the issue at about twenty international conferences on the basis of my comparative study of the Western psychoanalysis and the Eastern tradition of the Tao.

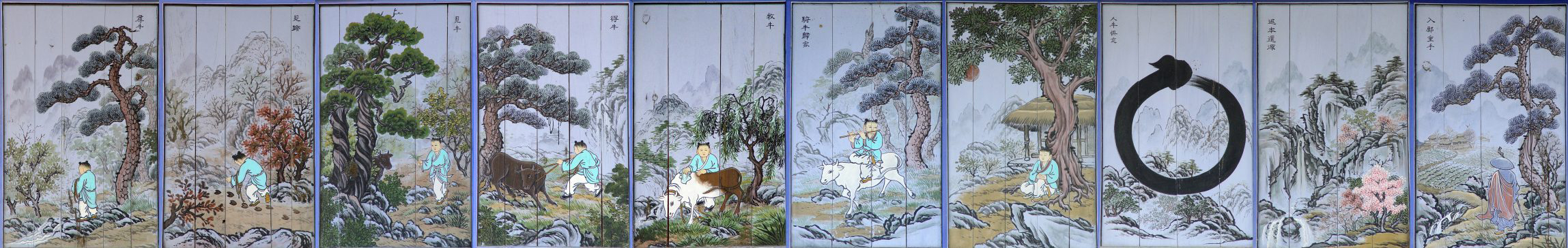

Seen from the perspective of our Tao tradition, the Western psychoanalysis falls much short of the ultimate solution provided by the Eastern tradition. For example, there is a famous Buddhist text called "Ten-Oxen-Pictures" describing ten stages of practice. The ultimate state there is that of "Herder and Ox Both Forgotten" or, in other words, the stage where ''There is neither object nor subject.'' The Western psychoanalysis can never reach it. It falls at best in the seventh stage of the Pictures, that of "The Ox Is Forgotten, but the Oxherder Is Still Present." It's because the Western psychoanalysis never gives up its attachment to human subject, while the highest stage can be reached only when self-attachment has been overcome. That's what I've found and tried to advocate to the West.

Some specialists in the Eastern philosophy would take the Tao as something beyond reality, so lofty for us to reach. But the Tao means Nature itself or, more simply, absence of desire. When we meet a person, we used to mistake the impression or idea we have of that person as what he really is. The Tao means elimination of that kind of mistake, and it can be achieved by removing distracting ideas and language from subject/object relation. Ideas and their linguistic expressions work as a barrier between you and the object, hindering appreciation of the true original nature of the reality. When that barrier has gone, the subject and the object become one. Then you yourself become, to say, a clear mirror that reflects the whole Reality as It is. This is the stage of so-called "total penetration of the Tao" or "completely mastering Tao."

Lao-tzu's Tao Te ching begins with a warning against the common mistake mentioned above: descriptions and names of the Tao are not the true Tao itself. We may talk about the Tao in indefinitely various ways. But all of them are nothing but mere indicators of the Tao or Reality. They are like a finger pointing to the Reality. We used to see only the finger, not the Reality it points, and think "That's the Tao!" This is the fundamental illusion of mankind. And it is desire that hinders us from seeing the true Reality directly. Therefore the philosophical and religious traditions of the East, whether Confucian or Buddhist, regard elimination of desire as their ultimate goal. To empty the mind of desire―that's the Tao. Empty mind can see people and things as they truly are. Insofar as you have desire, however slight it may be, you can never stop deceptive and artificial articulation of your idea or impression of the reality―people, things, social phenomena, etc. To mistake one's own idea of the reality as the reality itself―it is called ''projection'' in psychoanalysis. So called the ''Non-Doing," the ultimate goal of Eastern philosophy and religious practice, refers to the state of 'No Desire' or, in other words, of perfect personality. It never means ''doing nothing'' or mere inactivity.

MC: Do you mean that to empty the mind by eliminating desire from it is the Tao?

RHEE: Yes. To empty the mind―that's the Tao. Then you can see the Reality as it truly is.

MC: It seems that the idea of the Tao has been a major topic in our tradition all through its history. How did our ancestors understand its meaning?

RHEE: As I've said, and as Mr. MUN Il-p'yong pointed out in his book Korean Culture, the idea of Tao is so deep and lofty that even our ancestors rarely had full understanding of it. To see the Tao, you must first perfect your personality by, above all, eliminating all desire and thus emptying your mind. In any time and any place, few people succeed in attaining perfect personality. This was also true with our ancestors.

MC: Is there anything like the idea of the Tao in the Western philosophy or thought?

RHEE: Plato said in Phaedo and other dialogues that to see the Truth the mind should be purified first. The term ''catharsis'' refers to that kind of purification. He also said that the body should be overcome. Here ''body'' means, above all, emotion or desire. Socrates also said that the Truth could be reached only after death. On the other hand, Buddhism insists that so-called ''the concern in life and death'' should be overcome, and only then the mind can be emptied. That's the common aspect of the Western and the Eastern traditions. But the Western tradition has put emphasis on intellectual pursuit as the major method of purifying mind. All the Western civilizations have been based on that idea. Psychoanalysis is not an exception. But according to the Eastern tradition, intellect generates none other than illusory ideas and deceptions. Therefore the Eastern tradition insists that we should go beyond intellectual thoughts.

MC: It seems to me that there is no big difference between the West and the East in their understandings of the deepest nature of life, although their life styles may appear to be different.

RHEE: I must say you are right, but with some reserve. Some sectors of the Western philosophy has come close to the idea of the Tao, especially through Eckhart's mysticism and psychoanalysis in this century. As of today's movement, so-called the third psychology, the humanistic psychology the fourth psychology, or the transpersonal psychology completely comply with the idea of the Tao, at least in their theories. For an example, the humanistic psychology insists that the highest mentality can be attained only when self-attachment is overcome or, in other words, when the ego is transcended; and that kind of mentality is in the state being one with the universe. In this way, the concepts of the humanistic psychology appear to be very close to the Eastern idea of the Tao. Actually, some psychoanalysts began to be interested in Zen as early as 1930s and were much influenced by it.

MC: Then would you please make a comparison between the idea of the Tao and that of the Western psychoanalysis?

RHEE: Both in the Eastern tradition of the Tao and in the Western psychoanalysis, the very first step is to pull out everything in your mind so that it is emptied of any emotional residue. At first, in most cases, negative emotions so far oppressed would be expressed. When all of them are pulled out, then you get into the state of so-called the 180 degree as expressed by the Buddhist saying, "The mountain is not a mountain, the stream in not a stream."

MC: A file footage is on screen now. What does the saying mean?

RHEE: Suppose I'm treating a teenager patient. At first he'd say that his parents love him most, that they are the best parents in the whole world, and so forth. Then I'd say, "Pull out whatever feeling you have in your mind, whether good or bad, of your parents." After a while, he may express extreme hostility against his mother. The hostility may be so intense that he may have had a hidden wish to kill his mother. Mother, who has been taken as the symbol of love, is now the object of extreme hatred. This kind of complete reverse of value or absolute negation is called the 180 degree state. But once he has poured out all those negative feelings, memories of all the love his mother gave him comes back so that positive feelings of mother once again prevail. It's so-called the 360 degree state, as expressed the Buddhist saying, "The mountain is a mountain, the stream is a stream." It may appear to be identical with the original state before all the processes of treatment so far described. But there is a fundamental difference between the zero degree state and the 360 degree state: Having made a complete 360 degree turn, he is now in his true Self that embraces both negation and affirmation. In the zero degree state, negation was oppressed and therefore positive feelings were not grounded in full affirmation. It was not a true Self. The goal of Buddhist Zen practice is also to make that kind of complete 360 degree turn and find so-called the True Self or the Original Mind. But the Western psychoanalysis, as I said earlier, never go beyond the idea of Self as the undeniable subject of mental activities. That's the fundamental difference of psychoanalysis from the Eastern tradition of the Tao. The latter goes further, and aims at going beyond subjective ideas and self-attachment to the state where there is no subject/object dichotomy.

MC: Then the idea of the Tao is that we can find our true selves by embracing both affirmation and negation.

They say all modern men, without exception, have mental disorder to some degrees. Would you please explain the significance of the Tao regarding the problems of modern civilization?

RHEE: When we say "modern civilization," we used to refer to the Western civilization―as if there were no other civilization. Anyhow, Lewis Mumford, an American philosopher, said in his book Human Condition that the history of the Western civilization since Renaissance has been that of destructive desire. Many of us are misled to think that Renaissance was a liberation of Self. But seen from psychoanalytical point of view, Renaissance was indeed a liberation of human instinctual desires and thus diminution of the true Self. It was a liberation of the selfish desire for conquest―conquest of other nations, nature, and other people.

MC: You mean predominance of collective selfishness.

RHEE: Yes. But the exploitation of the selfish desire for conquest is sure to end up with being conquered. For example, we have been exploiting nature to fulfill our selfish desires. But now nature has begun to revenge us for it. We are about to be conquered by nature.

MC: By nature!

RHEE: Yes. by nature! And it means an overall destruction of mankind. How can we solve this problem? Lewis Mumford suggests that the solution be in self- examination or self-control of mankind. This is not different from emphasis on self-control and negation of desire in the Eastern tradition. And it is same as saying that realization of the Tao is the sole and final solution of all the problems of modern Western civilization. Psychoanalysis or counselling also aims at attaining the ability of self-control. Of course, Mumford didn't know the Eastern tradition of the Tao. But self-examination or self-control he advocated is actually the practice of the Tao. In Confucian terminology, it is "To Overcome Self"; and in Buddhist terminology, "To Be the Master of Self." To be the master of Self―that's the Tao. On the contrary, to be swayed by personal feelings and emotions―that's what we call neurosis.

MC: Isn't it true that one of the most fundamental fear we have is that of death?

RHEE: Yes.

MC: How is death explained in the Tao tradition?

RHEE: Here again is an essential difference between the Western tradition and the Eastern tradition. As Paul Tillich pointed out in his book Courage To Be, psychoanalysis and other Western ways of treating mental problems can relieve neurotic fear, but not the ontological fear. The ontological fear is shared by everybody. You can liberate yourself from it only by realizing the Tao. When you don't have so-called "the Mind of Life and Death," you can face death without fear accepting it as a normal process of life. That's the ultimate and total transcendence of death. You know that Koreans have had the custom of preparing their own tombs and coffins while they are alive. The Westerners would think it's weird. But I heard that some Americans also do the same thing nowadays. So-called the existentialist philosophy of the West indeed is based on the concern in the issue of the ontological fear. But they could never get the ultimate solution. The ultimate solution is in the practice of the Tao.

MC: In short, you mean that we can overcome the fear of death and thus accept death by practicing the Tao.

RHEE: And vice versa. Only when death is accepted, the mind is emptied. As long as we have fear of death, we can't see the Reality as it is.

MC: It is said that one of the essential features of the Eastern philosophy has been the idea of the Tao...

RHEE: But seen from the perspective of the Tao, ideas are nothing but deceptive illusions. We may even say that to get rid of ideas is the Tao. The whole reality as it is here and now, not artificially constructed ideas of it, is The Tao.

MC: Then we shouldn't say "the idea of the Tao" but simply "the Tao."

RHEE: The point is that the Tao is not something separate from reality. It is not ideas.

MC: I guess our ancestors' lives were much influenced by the Tao tradition. Were they?

RHEE: Yes, they always were. In 1979, I visited a psychoanalyst at London University, and asked him of the difference between Western and Eastern patients.

MC: Is there any difference?

RHEE: Yes, he told me of a very interesting difference: the Asian patients were much concerned with their previous lives while the Western patients were much concerned with the present, especially with doing something. This implies a very substantial difference between the East and West.

MC: How?

RHEE: According to Erich Fromm's work To Have or To Be?, "To Be" is to be concerned in how to live, how to die, and what to be. But the major concern of the Western civilization has been "To Have," hence all its neurotic features. The desire to have something or to do something generates neurosis. Lao-tzu meant it with the concept "Doing," in contrast to "Non-Doing." "Doing" is the same as neurosis in the sense that both are grounded in desires. On the contrary, "Non-Doing" means "to be natural" without manipulating reality according to one's own desires.

MC: Then can we say that "To Be," not "To Have," is a search for the true Self?

RHEE: Yes. And that's none other than the Tao. Trying to do or to have something is to be against the Tao, for that kind of activities are based on desire.

MC: Some people tend to say that any method can be justified only if the goal is good. Furthermore, there are many instances that the moral value of the goal is not even checked. It seems that many social problems are generated from that tendency. Would you please say something about it in terms of the Tao?

RHEE: To make money or to get high social status itself is not bad. It's good to be able to spend money for other people thanks to one's wealth, or to serve many people thanks to one's status of high social responsibility. But as Confucius said, "To become rich or to get a high status in an unjust way is worthless." But to do so in a right way―that's good.

Then the question is, "How can we do it in right ways?" To know what's right and what's wrong, we must do complete self-examination first of all. But our history testifies that Korean people have lacked serious self-examination. Most troubles our nation has suffered are due to her people's negligence of self-examination. Troubles we have suffered in foreign relations are good examples. Our history is full of the incidents of foreign invasions, but we've never done serious reflection on them and therefore kept on being vulnerable. For an example, our nation suffered enormously due to the Japanese invasion and subsequent seven year war at the end of sixteenth century. The whole country was almost devastated, but anyhow managed to survive. We should have learned a lesson and got prepared never to repeat the same experience. But about four hundred years after that, in 1910, we were at last annexed by Japan losing independent sovereignty. The same problem is found in our attitude in relations with other foreign countries such as China, Russia, and so forth.

As is often discussed by mass media nowadays, the United States military government, established in South Korea right after the end of World War II, at first tried to employ officers of the former Japanese colonial regime again in government positions. And then came RHEE Seyng-man, the first president of the Republic of Korea. He and his men, in order to hold their political power, employed cooperators of Japanese colonial regime and disbanded so-called the Special Committee for Investigation of Infidels. The other countries, after World War II at the latest, took much effort to educate their people of the Japanese ways and of how to deal with them. But we've never done it for all the atrocities we experienced. We don't even the very basic self-examination in foreign relations as well as in individuals' lives.

MC: There have been many campaigns for realization of justice in our society...

RHEE: All are in vain unless complete self-examination is done first.

MC: Paradoxically, they seem to reflect the decay of morality, for there wouldn't be that many campaigns for recovery of morality if it were not felt to have decayed.

Next, would you please explain the relationship between the modern scientific civilization and the idea of the Tao?

RHEE: To guide our own academic, political, economic, and other activities to a right direction in regard of the reality of our own nation, we must have, first of all, a clear understanding of what science is and the difference between the West and the East. But so far we have a lot of confusions regarding those issues.

I should have mentioned this at the very beginning of this conversation: There is a fundamental difference between "Learning" and "the Tao". Learning is a matter of textual studies, thoughts, language, theories, etc., while the Tao is beyond them. For an example, Buddhist monks are classified into two categories: those who specialize in doctrinal studies on one hand, and those who are devoted to the practice of the Tao on the other. But we have been educated only in the former following the Western tradition and forgot all about the latter tradition.

MC: I guess the revival of the Tao tradition would have much significance to the solution of problems of modern civilization.

RHEE: It would be the ultimate solution of all the problems of modern civilization for the sake of the whole world as well as of our country. As Dr. William Barrett, an American philosopher, pointed out, the Tao tradition will help Western thinkers to liberate themselves from the conceptual prison provided by Plato that has been binding them.

As of the modern scientific civilization, we used to confuse scientific technology with science proper. When we say "science," we used to mean "scientific technology." The Western tradition of science in its essence has been an effort to understand nature, and has shared some common ground with the Tao tradition. But that original feature of science is forgotten now. Science as mere technology is a method of conquering, not understanding, nature. To conquer or rule over somebody, you don't have to understand that person. You just need to know his weak points. If his weak point is that he is never able to refuse money, then you offer him money. Then you can conquer him without having any understanding of his true nature at all. That's exactly the way of scientific technology. It inevitably entails destruction. Since quite a while ago, there has been efforts to humanize science in the West. Humanization of science is equivalent to realization of the Tao in science. That would be the ideal relationship of science and the Tao.

MC: As a conclusion, would you please give advice to the audience, especially the youth?

RHEE: Several years ago, over the period of about three years, I gave lectures on the national identity(subjectivity) to diplomats as a part of an educational program in an institution. What I've found is that the old generation has less confidence in the national identity(subjectivity) than the young. It's a remnant of the effect of Japanese colonial education. When it comes to the youngsters of around twenty, about seven out of ten show strong confidence in the national identity (subjectivity), while the other three are still the same as the old generation.

Our young generation should be aware of the hazardous remnants of the Japanese colonial education that the old generation carry with them, make efforts not to be contaminated by them, and never inherit their groundless hatred of our own traditional culture. It is much encouraging that nowadays many young people are eager to learn our tradition, especially because I think our tradition is all about the Tao. Tan'gun mythology is a good example. It is a story of the Tao: the bear practiced the Tao and thus became human female so as to beget Tan'gun, the founder of Korean nation. Therefore we may say that our tradition of national identity(subjectivity) started with the Tao. Another example is T'aegūkki (Tai Chi Flag), our national flag. A college professor said that its design is too complicate and thus should be replaced with a new simpler one. His idea is totally due to his ignorance of the deep meaning of T'aegūk. T'aegūk represents the Tao. Many foreigners, once learning about its meaning, express their jealousy of our national flag. The Tao is peace and harmony. Hence the ideology with which Tan'gun founded the first Korean nation: "To benefit all human beings." Concern in human prevailed our tradition all through its history. I hope our young generations keep this deep in their hearts in order to be the creators of a new human civilization that will be based upon meeting of the Far East traditional culture and the Western scientific culture as Prof. Reischauer predicted a few years ago.

#Attachment

- E_WHAT IS THE TAO.hwp (73.0K)

- PrevThe Tao and Empathy : East Asian Interpretation 25.05.20

- NextICOP Opening Address 25.05.20

댓글목록

등록된 댓글이 없습니다.